The pandemic caused a sharp rise in warehouse demand, driven by a change in inventory strategy from just-in-time to just-in-case. Should the Department of Defense (DoD) also shift to keeping more supplies ready in storage? The DoD maintains stockpiles of weapons, food, and repair parts in various locations around the world. If they don’t have these supplies when and where they need them, the impact is more than just financial—they are more cautious about risk compared to private businesses.

A just-in-time inventory approach aims to keep the smallest amount of stock possible while still meeting mission needs. On the other side, a just-in-case strategy—recently more popular—means ordering extra supplies each time, just in case they’re needed later. This approach requires spending more money upfront to buy and store goods, but it improves readiness since the items will already be on hand where and when they’re needed.

Both strategies have their downsides, and the best approach often falls somewhere in between. The right method depends on the unique needs of each product. Before going into product-specific guidelines, let’s look at the risks of leaning too far toward either just-in-time or just-in-case inventory.

Drawbacks of Just-In-Time Inventory

A pure just-in-time system means ordering items only when needed from the manufacturer. The biggest problems include slower response times, less time for quality checks, and higher production and shipping costs.

Slower response to urgent needs

Quick response is critical for the DoD, whether it’s for disaster relief or responding to attacks. The first few days are often the most important. However, it can take weeks or months to place orders, make the parts, and deliver them to the right location.

This delay is the main reason a fully just-in-time approach is risky for the DoD—it can hurt readiness. The defense supply network can’t always make and deliver supplies quickly enough to meet urgent demands.

Little time for quality checks

When speed is the priority, steps in the production and delivery process may be skipped—often quality control. In emergencies like wartime or relief operations, there might not be time to confirm that parts meet standards. If items go directly from the factory to the field, there’s no chance for others to inspect them. This means equipment is used right away with the hope it works correctly. It also creates an opening for bad actors to intentionally deliver faulty parts.

Higher production and shipping costs

Just-in-time often requires shipping goods quickly, often by expensive methods like air freight. If the equipment is made in only a few locations—or just one—it’s unlikely to be near where it’s needed.

Manufacturers also charge extra for rush orders, and factories may have to pause other work to fulfill them. Producing in large batches saves money, but smaller urgent orders reduce efficiency and raise costs.

Drawbacks of Just-In-Case Inventory

Keeping large amounts of stock in storage creates its own challenges, including high upfront spending, ongoing costs to manage warehouses, and the risk that items will expire or degrade.

Large upfront spending

Buying and storing lots of inventory ties up money that could be spent on higher-priority needs. If the items are used within a few years, it’s worth it. But if they expire or become outdated, it’s wasted money. Stockpiling also means spending more to build or rent storage facilities.

Ongoing maintenance costs

More inventory means more warehouse space and more costs to operate it. Staff and equipment are needed to move, track, and protect items. Over time, warehouses can become cluttered, making it harder to find what’s needed and increasing costs. Even unused items require regular checks to make sure they’re in working condition.

Shelf-life problems

Items stored for too long can lose effectiveness. For example, reports suggested that some of Russia’s equipment failed in the early stages of the Ukraine invasion because tires had rotted and rations had expired. Other issues like rust, moisture damage, and temperature changes can harm stored goods. Climate-controlled warehouses can slow this damage, but they cost more to build and operate.

Finding the Right Balance

Some situations favor a just-in-time approach, others a just-in-case approach. There’s no one strategy that works for all products. Below are guidelines for when a just-in-case method might make more sense. Items that don’t fit these cases might be better suited for just-in-time.

High-cost items

When ordering large quantities with enough lead time, manufacturers can offer lower prices by producing in efficient batches. This can make it worthwhile to store extra high-cost items. For cheaper items, storage costs may outweigh production savings—unless they also meet other criteria.

Long lead time items

Items that take a long time to produce or source are risky to manage with a just-in-time method. Limited suppliers or complex manufacturing processes can cause delays. When lead times are long and unpredictable, it’s safer to keep extra stock on hand.

High-priority items

Items critical to a mission’s success should be stocked in surplus. Keeping them at multiple locations near where they’re needed helps reduce transport time and the risk of running out if one site is compromised.

Lower-cost, short-lead-time, and lower-priority items are better suited for just-in-time management since small delays won’t harm mission success.

Strategic Inventory for Any Supply Chain

Choosing between just-in-time and just-in-case depends on several factors. The goal is to keep enough inventory to maintain readiness while also managing costs. While this discussion focuses on military needs, the same principles apply to other essential supply chains.

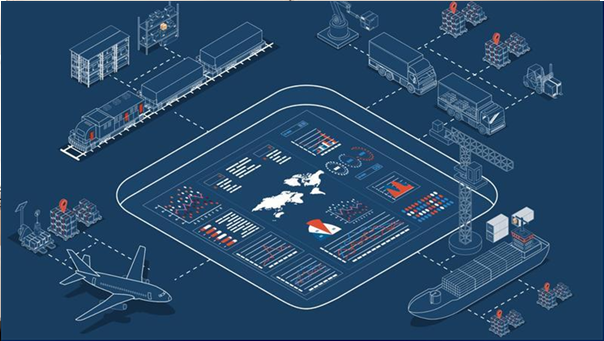

Using technology to determine optimal stock levels and storage locations is key. The right tools will consider cost, lead time, priority, and other factors to recommend the best strategy for each item.